On April 9, a concert of prayer and worship will rise coast to coast in America. Many thousands will gather for UnitedCry DC16 at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., while in Los Angeles, at the same time churches will come together at AzusaNow.

It will be a pilgrimage for many, a sacrifice of a Saturday. Yet driving a few hundred miles pales in comparison to how our forerunners offered themselves to seek God. Where true discipleship will be found—or lost—is what happens when we return home to our local churches and communities.

Today we call it a global prayer movement. For centuries it was referred to as monasticism. Today we call them Houses of Prayer, or HOPs. For centuries they have been called monasteries. We call ourselves intercessory missionaries. For centuries our types were known as monks.

At every point and place where Christianity came into crisis or compromise, God raised up a prayer movement, a new monasticism or faithful praying remnant to ensure that discipleship, grace and the gospel were kept pure.

Most notably in the third century, when Christianity became easy, grace cheap and the path wide, holy men and women went out into the dry places and deserts to die to self, stay pure, encounter God and learn to love Him and obey—radically obey. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire into the Medieval Period it was the monks of Ireland who literally saved civilization (How the Irish Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill is a good read.)

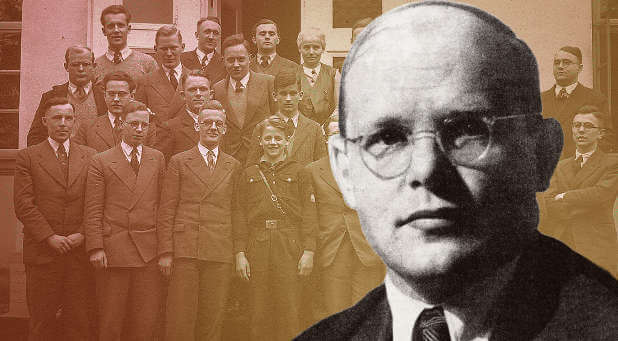

Hung by his neck in a German concentration camp, pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s vision of “a new monasticism” also suffered an early martyrdom of sorts. Eight years earlier, Bonhoeffer was leading an underground seminary in a chilly remote place called Finkenwalde Seminary.

There he taught what we know today as his book The Cost of Discipleship, much of which is a commentary on the Sermon on the Mount. There, he and his students lived in community the daily rhythms of life and prayer, which is spelled out for us in his short book Life Together.

In a letter to his brother Karl-Friedrick, dated Jan. 14, 1935, he made a very prophetic and important statement that many of us have adopted today as our guiding charge:

“The renewal of the church will come from a new type of monasticism which only has in common with the old an uncompromising allegiance to the Sermon on the Mount. It is high time people banded together to do this.”

For Bonhoeffer, the Finkenwalde rule included life together in authentic Christian community—or in his words, banding together. In a 1936 letter to the Finkenwalde community, Bonhoeffer noted that it also included “assembling together every day in the old way to pray, to read the Bible and to praise our God.”

This illegal seminary at Finkenwalde was both a school of prayer and a singing seminary; the daily prayer rhythms and worship life of ancient monastic orders he revived in fresh form. The foundation of the curriculum was “The Discipleship of Christ” as given in the Sermon on the Mount:

“The next generation of pastors, these days, ought to be trained entirely in church-monastic schools where pure doctrine, the Sermon on the Mount and worship are taken seriously—none of which are at the university and cannot be under the present circumstances.”

Bonhoeffer became captivated by and fascinated with Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount as the expectation Christ had of His followers. Bonhoeffer saw “these words of mine” in Matthew 5-7 as foundational for the Christian life and putting them into practice to be the key to successfully weathering the storms to come.

The Sermon on the Mount ethic of enemy love was to Bonhoeffer the summit of the mount, and his seminary at Finkenwalde was a training outpost for Christlike passive resistors. He trained his students to use spiritual weapons and not take up the world’s weapons of war.

The crucible of political hostility and societal animosity toward Christians is definitely on the rise in the world and it tends to produce a purer discipleship. And even though it only existed for two years before being shut down by the Gestapo, Bonhoeffer’s illegal seminary at Finkenwalde was a snapshot of Bonhoeffer’s prophetic vision of the essence of discipleship training within the context of a new monasticism resulting in the renewal of the church.

In our day, when church leaders more resemble CEOs and celebrities than self-denying devotees of Jesus, and in our day, when religious liberties are increasingly in peril again, Bonhoeffer’s model at Finkenwalde is truly a call back to the fundamentals of Christian discipleship, Christian community, a daily rhythm of prayer, an application of Sermon-on-the-Mount lifestyles and ethics.

The UnitedCry DC16 prayer gathering on April 9 will call specific attention to Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was hanged by the Nazi regime on April 9, 1945—a pacifist who nonetheless played a role in a covert attempt to bring down Adolf Hitler. Bonhoeffer’s commitment to seek renewal in the church, stay engaged in the public square and preserve his flock from compromise during crisis serves as a model for us all.

A book I’ve been recommending to those in our house of prayer is Punkmonk by Andy Freeman and Pete Greig. The title conveys how today’s monks in 24/7 prayer and furnace rooms in the major cities of the world look more like a pierced and tattooed generation of youth.

The monks of the earlier centuries looked different too. It’s no different than what our friend Lou Engle is calling us to with the Nazirite vow. It is my intention here to open our eyes to the breadth of what the prayer movement looks like in the world today. It spans all the traditions, as noted in Punk Monk:

To keep the discipline and perseverance required to pray continually means that you begin to experience different styles and types of prayer: New models, ancient disciplines, silence, liturgy, open prayer, prophetic prayer. Our prayer flows in rhythms.

I want to reawaken the contemplative you if the contemplative you isn’t already awake. There are daily rhythms of prayer and communion and encounter with God that we must never step out of. Far back into Judaism, and far back into Christian history, the faithful had set times for prayer and set prayers for those times—and there was a unison chorus.

Spirituality is very varied, and there is a time and place for all kinds of praying and expression. Many reading this are no doubt fluent in things like authoritative and warfare prayer, healing prayer, intercession, declarations, binding and loosing and so on.

But the ancient spiritual disciplines need to be reawakened too: meditation, fasting, study, simplicity, silence, solitude, submission, service, confession and worship. Our spirituality needs to become wider and deeper. It will take a deep root in God to withstand the days to come!

A native of Kansas City, Steve Hickey is pastor emeritus of Church at the Gate in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and a former South Dakota legislator. He and Kristen live in Scotland where he is doing post-graduate work at the University of Aberdeen on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the forerunner at Finkenwalde. He’s written several books including Obtainable Expectations: Timely Exposition of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount and The Fall Away Factor.

Reprinted with permission from Justice House of Prayer DC.