It was December 2013, and our ministry had organized an unprecedented event in Plano, Texas. Just prior to the meeting we had acquired some rare Egyptian artifacts that were between 1,600 and 2,200 years old. Our hope was that hidden within them we would find fragments of ancient scriptural writings.

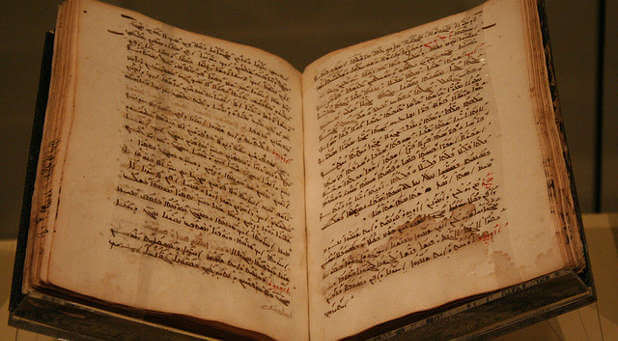

It wasn’t the artifacts themselves that interested me; it was their infrastructure, which comprised layers of papyrus dating to between the third century B.C. and the fifth century A.D. Papyrus is the paper-like substance used as writing paper in the ancient Middle East, including during the time of Christ. The plan was that during the Plano event we would discover whether papyrus fragments of scriptural writings were hidden within these artifacts.

When papyrus documents began to deteriorate or the writing started to fade, the information was copied onto new papyri and the originals were discarded. This was true, as well, of the original writings of the apostles. But because the ancients didn’t live in a throwaway society like we do today, they didn’t trash or destroy anything that could be used again or repaired. Instead, they found new uses for it. Discarded pieces of papyrus were often recycled by dampening them and pressing them together to form new items.

For example, Egyptian mortuary priests used discarded papyri to form papier-mâché, which they used as the infrastructure for mummy coverings and other objects. They sometimes covered the papyrus mold with plaster and painted it with silver or gold. To visualize the process, think of tearing the pages out of a worn book, wetting them, and pasting them onto the face of a department store mannequin, shaping the nose, brow, lips, and ears. After the paper dried, you could then add lacquer and paint to create a mask.

This papier-mâché technique was also used to create various other things, such as decorative panels, reinforcements for book covers and bindings and even household items.

In 2011, at a small seminar at Baylor University, I met Dr. Scott Carroll, a specialist in ancient languages and manuscripts. He had developed a proprietary method for carefully dismantling papyri from the inside structures of ancient Egyptian mummy coverings (called cartonnage) to discover what might be written on the papyrus surfaces. This extraction process led to some extraordinary discoveries of ancient classical and biblical texts.

I was fascinated by Scott’s work. His research and many contacts within the field of ancient and medieval manuscript study gave him a unique understanding of what to look for. Rather than searching for manuscripts at archaeological dig sites, Scott sought to legally obtain ancient cartonnage that had an infrastructure composed largely of discarded papyri.

The Egyptian artifacts I saw Scott dismantling at Baylor were made of pressed layers of papyrus. Our ministry subsequently commissioned Scott to locate one or more similar items in the hopes that we would find biblical writings on the papyri from which the papier-mâché cartonnage was made.

Eventually, Scott found for us what he believed to be a good specimen. Rather than rushing to extract the papyri from these ancient artifacts, we decided to create an experience so that other people could learn from the process as well. We invited two hundred apologists, Christian leaders, lay people, and highly specialized scholars in ancient languages to Plano for what became the Discover the Evidence event.

When the seminar convened, we watched for two days while a team of experts carefully dismantled the pieces. Finally, after lunch on Dec. 6, 2013, the moment of truth arrived. Scott Carroll was ready to announce his findings—surrounded by a gallery of 200 people who, like me, were eagerly anticipating what was about to be revealed. Seated no more than 15 feet away from the table at which the trained specialists had been working for hours, I could clearly see the many papyrus fragments laid out on the surface. Language scholars with magnifying glasses were huddled over the pieces.

As the crowd settled in, Scott cleared his voice. “Let me start with Josh’s stuff.”

Talk about a tense moment! I was trying to be calm. My grandson was sitting on my lap. Dottie, my wife, was seated to my right, and one of my colleagues was to my left. I was nervous, really nervous. With my eyes tightly shut, I prayed that we would have at least one small fragment of an ancient New Testament manuscript.

Scott carefully picked up a papyrus fragment with a pair of tweezers and looked toward me. I took a deep breath.

“Here is a paraphrase of the Gospels—a biblical Coptic text—fourth century.” My colleague took hold of my arm and said nothing. I simply took another deep breath, looked toward the ceiling, and whispered, “Yes! Thank you, Lord!”

Scott set the fragment down and picked up another. “Here is a second text from the Gospel of Mark, three lines … very nice biblical, unsealed, uncial text.”

He repeated this process again and again. After the initial analysis and identification was made, we found that we were the stewards of six ancient New Testament passages and one Old Testament manuscript fragment—seven treasures in all! While all the manuscripts are yet unpublished and must be further scrutinized to determine the exact content and more precise dating, we do know what passages these are from and the approximate time period. These included a manuscript fragment from Jeremiah 33, which was possibly the earliest known Coptic papyrus of this passage in existence today. There were also manuscripts of Mark 15, John 14, Matthew 6 and 7, and 1 John 2—all possibly the earliest papyrus records of these passages in any language in existence today—and Galatians 4, which dates as one of the earliest known papyrus passages ever recorded. These treasures were far beyond my expectations. I was utterly elated.

I walked to the table and gazed at the tan-colored fragments. As I lightly touched them, a wave of emotion swept over me. God had actually answered my prayer. I was humbled that he would allow me to share these treasures with the world. It reminded me of the emotions I had felt as a 19-year-old skeptic when I set eyes for the very first time on an ancient biblical manuscript in Glasgow, Scotland.

I traveled to Europe as a rebellious university student in an attempt to prove to a group of Christian students that their faith in Christ and the Bible was both foolish and unfounded. When I scoffed at them, they challenged me to examine the evidence that the Bible was reliable and that Christ was who he claimed to be. I accepted that challenge in pride, and my journey began at the Glasgow University Library where I examined ancient New Testament manuscripts.

I made my way from the libraries and museums of Scotland to the English libraries of Cambridge, Oxford, and Manchester. I studied the ancient manuscripts housed there, including the earliest known manuscripts, at the time, of the New Testament. Before my journey was over, I spent months researching at universities in Germany, France and Switzerland.

After devouring dozens of books and speaking with leading scholars, I ended up at the Evangelical Library on Chiltern Street in London. It was about 6:30 in the evening. I pushed the many books aside that were gathered around me. Leaning back in my chair, I stared up at the ceiling and spoke these words aloud without even thinking: “It’s true!” I repeated them two more times. “It’s true. It really is true!”

A flood of emotions swept over me as I realized that the biblical record of Christ’s life, death and resurrection was recorded accurately and was, in fact, true. The truth that Christ was God’s Son penetrated deep into my soul. I could no longer reject the reality of Christ and be intellectually honest with myself. The impact of that realization was truly a defining moment for me.

I now recognized that I was not rejecting Christ for any intellectual reason but for emotional reasons. I was slowly coming to grips with my rebellion and rejection of Christianity. I began to see that my life of sin was standing between me and a loving God who had sent his Son to die in my place. The power and profound meaning of those ancient manuscripts brought me face-to-face with the person of truth, and his name was Jesus.

The Hebrew writer said, “the word of God is alive and powerful” (Heb. 4:12). The Bible is no ordinary book. Although written thousands of years ago it is a living document. In the next installment of this series I will share with you how to know with confidence the Bible you read today is powerful and alive.

The preceding was Part 1 of a series and excerpted from Josh McDowell’s book, God-Breathed, published by Shiloh Run Press 2015. Stay tuned Thursday for part two. For more information and to receive a free download of the God-Breathed booklet, go to readgodbreathed.com.

Josh McDowell is a Christian apologist, evangelist and writer who has penned nearly 115 books.