No one knows the exact number of Cambodians that were executed in the infamous killing fields between 1975 and 1979. Estimates range between 1.7 million and 2.5 million innocent men, women and children who were mercilessly slaughtered at the hands of the Khmer Rouge regime.

But for Reaksa Himm, the only relevant number is 13. That number represents how many family members he personally lost in the killing fields. Among those 13 family members were his father, his mother and nine brothers and sisters. To compound the tragedy, Himm witnessed the brutal murder of 10 of his loved ones just outside a small village called Thlok.

That Himm survived the mass execution is nothing less than a miracle. But no less incredible is long trek he took from revenge to forgiveness.

Journey to the Killing Fields

Himm’s road to spiritual revelation was paved with unfathomable pain and heartache. But it didn’t start out that way. In 1975, Himm and his family were living a peaceful life in the city of Siem Reap despite an ongoing conflict between the ruling democratic leadership and the Khmer Communists led by brutal warlord Pol Pot. When the Khmer army defeated the American-backed government, Himm’s world was turned upside down.

After systematically executing all leaders sympathetic to the previous government, the Khmer Rouge regime began rounding up the Cambodian people and sending them to work camps. They were told they would only be gone three days to allow the army to root out American solders they suspected were still in hiding. But days turned to months, and months turned to years.

For the first two years, Himm’s family tried to conform to the new government’s policies. They never dared say anything against the leadership.

“If you opposed them, they would usually come in the night and tell you they wanted to send you to school so you could change your behavior,” Himm says. “But to be sent to school literally meant execution.”

By the age of 14, Himm was working in the fields tending to cattle and water buffalo. Each morning he would take some rice and dried fish wrapped in a banana leaf for lunch and head to his post. But one afternoon, he met an older man who was a stranger. The man asked if he would share his lunch. As part of the Cambodian culture, Himm had been trained to respect his elders, so he gave the man half his lunch.

“Before I knew it, he had eaten all of my lunch,” Himm recalls. “I was so angry. I had nothing to eat after that. But then he wanted to tell me a story. So I sat down and listened to him.”

“In the next six months,” the man said, “all of your family is going to be killed, but you will not die. You will have to go through a lot of suffering.”

Out of the Grave

A few weeks later, three Khmer soldiers came to the family’s house and arrested Himm’s father. When asked what he had done wrong, one soldier barked these ominous words: “Today we will destroy you! If we keep you, we gain nothing! If we kill you, we lose nothing! You are serving the American government! You are CIA!”

Himm had no idea what “CIA” meant, but he did know what happened to those faced with that accusation.

“That person became dead meat,” he says.

Himm ran back to his house and tried to gather his younger brothers and sisters. Suddenly the soldiers busted through the door, dragging Himm’s father behind them. At first the soldiers put Himm’s hands behind his back, but then they released him so he could carry his 2-year-old brother.

And then they took them all to the jungle.

“When we finally arrived, the soldiers began digging graves for us,” Himm says. “For the next 15 minutes, we just stood there and waited for them to kill us. I tried to hug my father, but his arms were behind his back. Then I told him goodbye. My father responded by saying something I will never forget. He said, ‘I love all of you.’ In Cambodian culture, we rarely show affection. That was the first and last time I heard my father say those words.”

Himm stood there as the soldiers made his father kneel down in front of the grave. His father was clubbed from behind and fell into the pit. Then came the screams.

“I saw every single ax fall as they butchered my father,” Himm says. “It was my turn, and I laid my baby brother beside me. Someone clubbed me from behind, and I fell on my father. Then I heard my baby brother scream so loud. Then I heard the chopping and the screaming.”

As the soldiers descended into the grave, they miraculously passed over Himm. When they noticed he was not yet dead, one of the men went back down and hit him again. Blood came through his nose and mouth. Himm began to suffocate and could hardly breathe.

“But no matter what, I didn’t move,” he says.

The soldiers left to find Himm’s mother and older sisters who were working on a farm back at the village. For the next 30 minutes, Himm struggled to climb through the bodies on top of him.

“At that time, I was just beginning to understand what had happened,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine how I could go on with my life. I was just lying there with the dead bodies and waiting for the soldiers to come finish me.”

Somehow he mustered the strength and courage to climb out of the grave. Had he stayed a few more minutes, the soldiers would have found him. Instead, he hid in the weeds and watched them drag his mother and sisters to the grave where they, too, were executed and dumped into the pit.

“After the soldiers left, I crawled back to the grave and knelt down and put my head to the grave,” he says. “I saw my mother’s face. I cried and screamed until I lost consciousness. When I woke up, it was about to become dark. I was by myself in the deep, dark jungle. That night, I decided to climb a tree and hold on to the tree the whole night. I couldn’t close my eyes. I was so scared.”

* * * * * * *

Forgiveness on the Big Screen

A story like Reaksa Himm’s is meant to be shared with a mass audience

The Cambodian killing fields have been well documented in books, television specials and films since the 1980s. The 1984 film adaptation of The Killing Fields, in fact, won three Academy Awards. But it was not until Reaksa Himm wrote the book Tears of My Soul that such a strong message of forgiveness and redemption emerged from the tragic historical account.

When Los Angeles-based producer Tim Anderson stumbled upon Himm’s book while searching for another book by the same title, he knew the amazing story was tailor-made for the big screen. “The true elements are beyond any fiction we as filmmakers could recreate,” Anderson says. “It seems the Lord wanted this man to survive for many reasons. We hope this film is one of those reasons. The world desperately needs the message of redeeming forgiveness.”

Anderson’s production company, BASH Media Group, is currently raising funds for a documentary film and full-length feature film intended for theatrical release.

“We hope both films inspire waves of forgiveness in people’s hearts, which will lead to reconciliation,” he says. “Forgiveness is unnatural, so we hope people will discover God’s supernatural attributes of forgiveness.”

Himm is likewise hopeful his story will have a significant impact.

“I don’t want the movie to just reach out to the Christians, but to anyone who needs to hear a story like this,” he says. “I hope the film will be a blessing and help people cope with bitterness and anger so they can forgive those who have hurt them.”

For more information on the Tears of My Soul film project, visit the official website at tearsfilm.com.

* * * * * * *

Three Promises

For the next three days and nights, Himm stayed there and cried. He survived by eating bamboo shoots and wild fruit and drinking dew squeezed from his blood-soaked shirt. After serious thoughts of going back to the village so the soldiers could put him out of his misery, the traumatized 14-year-old headed away from the gruesome site in search of help.

Before he left the killing field, though, he made three promises to himself. First, he would take revenge on his family’s killers. If he couldn’t do that, he would become a Buddhist monk to pay respect to his family. And if he couldn’t keep his first two promises, he would go far away from Cambodia.

Over the next two years, Himm migrated among a succession of refugee camps that at times proved anything but safe. He also reunited with the only other surviving members of his immediate family—his older sister Sopheap and her husband, Chhounly. When neighboring Vietnam overthrew the Khmer regime in early 1979, Himm returned to the city and lived with his aunt.

By 1984, Himm decided to join the police force. His purpose in doing so was simple: It would help him get back to the village where his family was killed so he could “eradicate every single person in that village,” he says, to pay honor to his family.

But when Himm finally had the chance to arrest one of the men who had helped kill his family, he couldn’t go through with it—despite dragging the man into the forest and aiming a gun at the man’s head. Having broken his first promise, Himm then faced the harsh reality that he couldn’t keep his second promise, as the current regime did not allow young men to become Buddhist monks.

“Finally, I tried to fulfill my last promise,” he says, “which was to escape from Cambodia.”

Free Indeed

Leaving Cambodia was both illegal and very dangerous. But Himm was desperate to leave his problems behind. He headed for Thailand, facing numerous life-threatening situations along the way, and eventually landed in the notorious Khao I Dang refugee camps. While there, he exchanged letters with a cousin who was living in California. Himm shared his desire to come to the United States, and his cousin, who was a Christian pastor, shared stories about his faith.

“He kept telling me about Jesus,” Himm says, “and I told him, ‘I need money, not Jesus!’”

Himm stayed in Thailand five years. His attempts to move to the United States were rejected by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Undaunted, he started a vigorous letter-writing campaign to the Canadian embassy. He also decided prayer wouldn’t hurt either.

“I felt hopeless,” he says. “One night I knelt on my knees and prayed, ‘God, if you take me to Canada, I will start a new life and live for You.’”

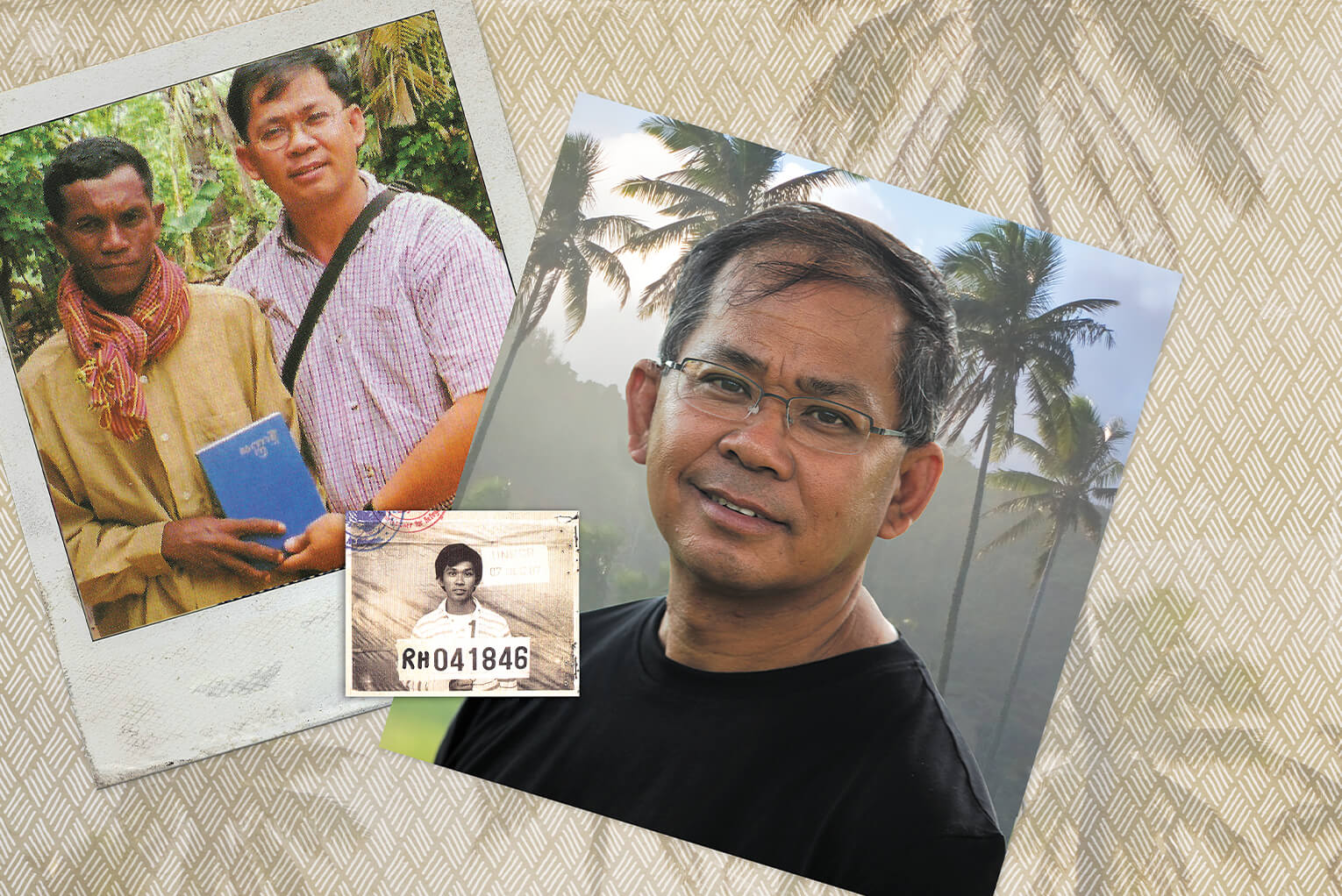

About 90 letters later, in 1989, Himm gained entrance to Canada. He accepted Christ a year later. Then he enrolled at Tyndale College in Ontario and earned a bachelor’s degree in religious studies, followed by a master’s degree in counseling and Christian education from Providence Theological Seminary.

Yet even as Himm was growing in his new life of faith, he still struggled with bitterness and hatred for his family’s killers, in addition to the depression and guilt he privately held on to because of his failure to avenge their deaths. The journey wasn’t easy, but gradually, as he studied God’s Word, passages such as Hebrews 12:15 (“See to it that no one falls short of the grace of God and that no bitter root grows up to cause trouble and defile many,” NIV) helped him realize that his failure to forgive was blinding him from seeing the grace of God in his own life.

As the Holy Spirit healed his deep wounds, Himm gained a revelation of both God’s justice from passages such as Romans 12:17-19 (“Do not repay anyone evil for evil. … ‘It is mine to avenge; I will repay,’ says the Lord”) and God’s forgiving grace (“Their sins and lawless acts I will remember no more,” Heb. 10:17).

“I had failed to allow God be the righteous judge,” Himm says in his book After the Heavy Rain. “Vengeance is the Lord’s, not mine. … God does not remember my sins anymore. God had cancelled all my sins, but I had failed to let go of the sins of my family’s killers.”

By 1999, Himm felt God calling him back to Cambodia. He returned to lecture on psychology at a Bible college but stayed to plant churches, including one where his family was killed. And while he had already forgiven the killers from abroad, he knew the time had come for him to take the process one step further.

Himm located the man who killed his father and siblings, the man who had clubbed him from behind, and the man who had killed his mother and older sisters. He came prepared.

“I offered each of them a camel scarf as a symbol of my forgiveness,” he says. “I offered my shirt as a symbol of my love for them. And I gave them a Bible as a symbol of my blessing for them.”

As Himm reflects on those powerful encounters, he is reminded of Jesus’ words found in John 8:36: “So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.” “To say ‘I forgive you’ from Canada to Cambodia was easy,” Himm says. “But to actually travel back and meet those killers and look into their eyes and say, ‘I forgive you,’ that was tremendously difficult. There’s no way in my own humanity I could have done that. It was only the power of the grace of God in my life that gave me the strength to do that. It was only God’s grace that set me free.”

Chad Bonham is a journalist, author and broadcast producer who has worked in mass media for more than 20 years. A regular contributor to Charisma, he recently published Life in the Fairway.